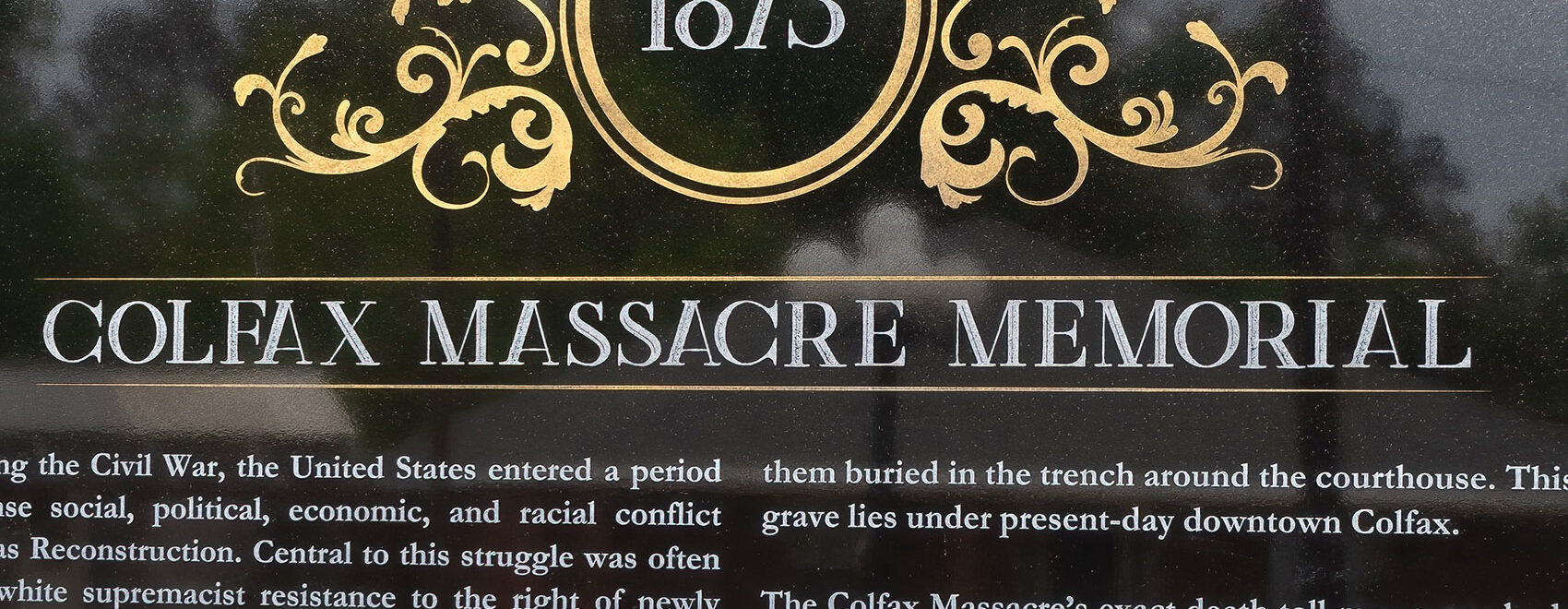

Colfax, a small town in northern Louisiana, has a new memorial to a massacre. The memorial commemorates a brutal and deadly racial massacre that occurred there in 1873. Almost 150 years later, the unveiling of the memorial marks an important step in recognizing and remembering the tragic event.

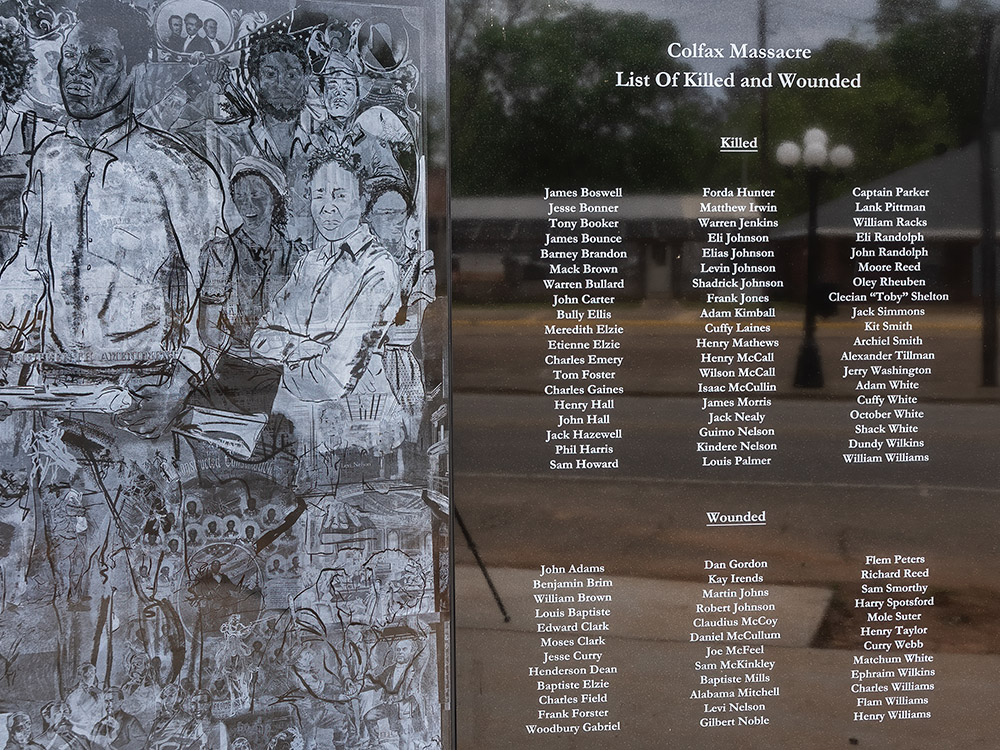

The Easter Sunday massacre remains the deadliest one-day event of the post-civil war reconstruction era. White supremacists killed nearly 100 black citizens in Colfax. The exact number of casualties is still unknown, but the new memorial includes the names of 57 black citizens known to have been killed, and an additional 36 names of black citizens who were wounded. The memorial also provides a detailed account of the brutal killings.

tv feature on the new colfax massacre memorial

“false and offensive” marker is gone

Louisiana Governor John Bel Edwards helped dedicate the new memorial in downtown Colfax, saying, “This day has been a long time coming”. The state of Louisiana had a responsibility to remove the old marker that portrayed the mass killing as a riot, which “ended carpetbag misrule in the South.” The old marker was “false and offensive”, according to Governor Edwards.

recognition for victims of massacre

Descendants of both the white perpetrators and black victims attended the dedication of the new memorial. Dorothy Richardson Peters pointed to one of the names on the marker, Henderson Dean, saying, “he was wounded. That was my great great great grandfather.” She added that she was never taught about the massacre in school, but her family always told her it was something “you didn’t talk about.”

a time for history and healing

Jerry Hickman, whose grandfather was one of the attackers, also attended the unveiling. He said, “The younger generation should grow up knowing the truth of the matter.” Several of the attackers were convicted of federal civil rights violations, but those convictions were overturned by the US Supreme Court in U.S. versus Cruikshank. That decision and others limited the ability of the federal government to enforce voting and civil rights for African Americans into the 1960s.

Rev. Avery Hamilton of Colfax, whose great-great-great grandfather was the first black killed in the massacre, was determined that their names would be carved in stone. He said, “People are going to know that their life mattered.” Hamilton, along with retired Houston businessman Dean Woods and the Colfax Memorial Organization, was able to raise the $65,000 needed to erect the new memorial. In the end, Governor Edwards summed up the significance of the new memorial best when he said, “When we changed the marker today, we didn’t change history. In fact, we acknowledged what the true history was.”

an unlikely bond removes a controversial marker

how to visit the colfax massacre memorial

The new Memorial is located in downtown Colfax, LA, along Louisiana Highway 158 near the railroad tracks, one block north of the intersection of Louisiana Highway 8, the Alexandria-Colfax Highway.

putting history on display

read the history on the new Colfax massacre memorial:

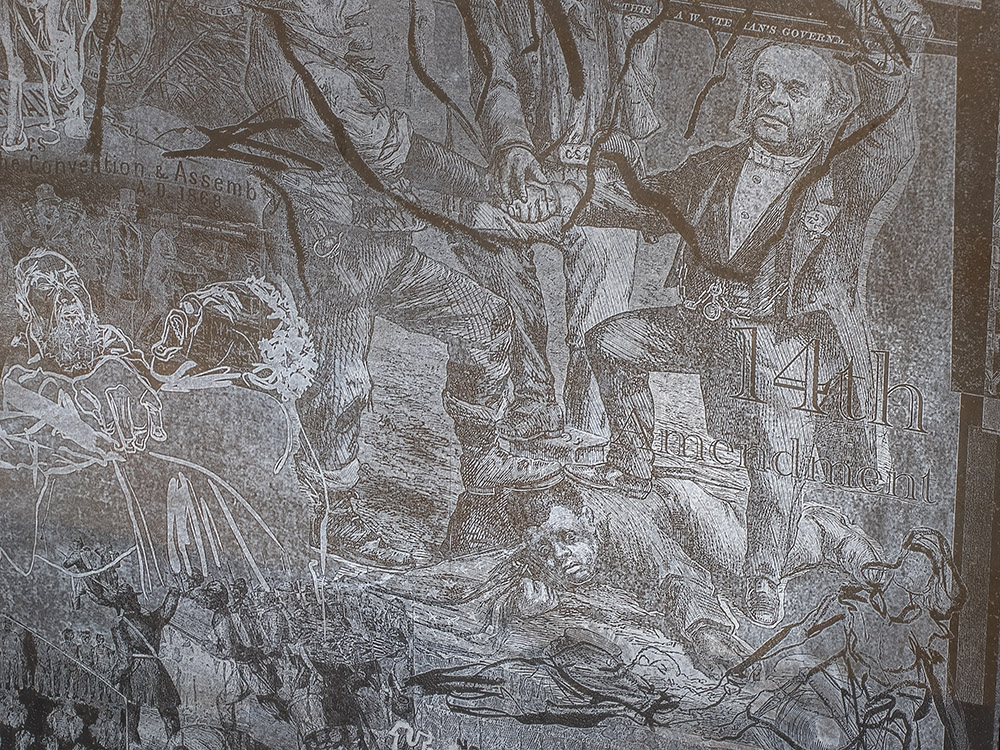

Following the Civil War, the United States entered a period of intense social, political, economic and racial conflict known as Reconstruction. Central to this struggle was often violent white supremacist resistance to the right of newly emancipated Black people to vote and hold office. The Colfax Massacre, which occurred near this site on April 13, 1873, was a crucial episode in this story. The bloodiest one-day event of Reconstruction, it had long-lasting legal and political repercussions for Louisiana and the entire country.

On that Easter Sunday, approximately 140 heavily armed white men from Grant and surrounding parishes, led by ex-Confederate officers, attacked a roughly equal number of Black men at the courthouse in Colfax. The attackers intended to install local officials whom they had tried to elect through fraud the previous November. The Black men had assembled with what weapons they owned or could hastily improvise, in defense of the parish’s rightfully elected officials, white and Black, who favored greater racial equality.

The courthouse the freedmen were trying to protect, like the territory of Grant Parish itself, had formerly been part of one of the South’s largest plantations. Only a few years earlier most of these Black defenders had been enslaved on that land. Intent on protecting their hard-won new freedom, they were also protecting their families, who had sought refuge in Colfax days earlier when white supremacist gunmen murdered a Black farmer, Jesse McKinney.

On the morning of April 13, the white supremacist leaders delivered an ultimatum. The women and children evacuated the courthouse. The attackers began firing on the courthouse shortly after noon. The freedmen withstood the onslaught for two hours, from a shallow defensive trench they had constructed. Then the white supremacist force opened fire with a small cannon, overwhelmed the defenders and set fire to the courthouse, where retreating Black men had taken cover.

The Black men were ordered to lay down their guns and surrender. As they emerged from the building, some waving white cloths and papers, they were fired upon. Others were chased, captured, and killed on the spot. Several bodies showed signs of repeated stabbing and beating. Later that evening, the white supremacists marched dozens of their remaining disarmed Black prisoners into fields near the courthouse and shot them in the head at close range.

They dead lay where they fell for two days until state and federal investigators arrived from New Orleans and ordered most of them buried in the trench around the courthouse. This mass grave lies under present-day downtown Colfax.

The Colfax Massacre’s exact death toll may never be known. Records of subsequent U.S. government investigations suggest a conservative estimate that between 62 and 80 Black men lost their lives that day. These murders on April 13, 1873 made up just part of a wave of terrorist violence against African Americans during the post-Civil War years that killed thousands of people. Including victims of the Massacre, more than 100 perished during Reconstruction in what is now Grant Parish.

Invoking new civil rights laws, the federal government under President Ulysses S. Grant tried to bring the authors of the Colfax Massacre to justice. Insufficient resources hampered the prosecution, as did active resistance from many in central Louisiana who sympathized with the perpetrators. Eventually, nine men were arrested and stood trial in a federal court at New Orleans. In June 1874, a jury convicted three – partly based on testimony from survivors and other Black witnesses, including women, who courageously told the story despite threats and intimidation.

The Supreme Court of the United States largely undid this limited victory for justice and the rule of law on March 27, 1876, when it reversed the three convictions and set the perpetrators free. The court’s ruling in the landmark case, United States v. Cruikshank, was one of several precedents set during, or soon after, Reconstruction that would constrain the federal government’s constitutional authority to enforce the civil and voting rights of African Americans. These precedents helped advocates of white supremacy to regain power in southern states and to keep it for decades.

No one ever received punishment for the Colfax Massacre. Some of those responsible went on to prominence in business, the professions, or government. Compounding their impunity was a subsequent campaign of falsification and distortion. The myths, perpetuated in books and inscribed on physical monuments, presented the men who committed the massacre as heroes and saviors. Three white members of the attacking force who died in the clash at the courthouse – two of them likely shot accidentally by their own side – were depicted as martyrs.

This memorial stands in recognition of truth about that terrible day and in loving memory of the heroes and martyrs who died defending their families, their rights, and their freedom.

Colfax massacre memorial location

8th St, Colfax, LA 71417

Wanda Bailey

Dave, thank you for making this horrific act and it’s untruthful past narrative and corrections available for the people of Colfax and Louisiana. Thank you for your work, I enjoy visiting Louisiana with you. Great Work!!!

Diane Stewart Harris

The monument is beautiful. Do you have any information about Richard Reed? To me, the sign about the massacre was not offensive but was significant to display about the event.

Debra G

Thank you for sharing this story. Two descendants from both sides come together to make this monument special and possible is powerful. It teaches the world that history should be told in its entirety as a reminder of what happened and how it happened matters. This is how stories should be taught!

Barbara Dixon

Thank you for sharing this part of history and for sharing it with truth. I think the thing that angers people more is not the history itself but when it’s told falsely. The truth is what makes you free. The truth also allows others to understand better and when one understands it helps them process differently. So, again thank you.

Osbern Sterling

Thank you so much for sharing this amazing part of our history! Do you know if there is any information on the people that were killed and wounded? Their are 5 names on the monument that are ancestors of mine and very little is known about them. Thank you and everyone associated with bringing this to life!!!